![]() Academy Beginnings

Academy Beginnings

![]() Ian D Cameron

Ian D Cameron

Ian Cameron was the prime mover behind the New Zealand Academy of Highland and National Dancing, although it was to devour him. He was a man of inherited Wairarapa sheep-based wealth with the archetypal attitudes associated with his type and time. He was not versed in any of the Scottish arts. He could be ingratiating or bullying or plain bad mannered as it suited his purposes. However, he was determined and was effective in organising the outcomes of meetings beforehand. He rewarded sycophants by increasing their influence and he applied his financial means to his objectives.

This assessment of Ian Cameron has been corroborated since the first edition of the memoir by a member of his family, by the late William Anderson, Dannevirke, a committee member of the Pipe Bands Association when Cameron was President of it and by a gun dog enthusiast John O. Macpherson, who remembers Cameron at gun dog trials as, "Being very free with his whisky but we all used to tip toe around for fear of offending him." Don Fitchett the Wanganui piper of Turakina connections found Ian Cameron to be a bully, according to his widow.

He is to be first found in 1926 advocating a confederation of Caledonian Societies, which did eventuate. Aggregating organizations with himself as president of the expanded body was a trait of his. By the early 1940s his energies were directed at establishing a national academy of piping and dancing under the auspices of the New Zealand Piping and Dancing Association, Ian Cameron President. He was successful in establishing the satellite but it soon became the sun about which the Piping and Dancing Association revolved, eclipsing the luminary Cameron.

![]() Frances Cameron and May Thorne Wilson

Frances Cameron and May Thorne Wilson

Cameron, in effect, appointed his wife Fassie McDougall-Cameron as the principal dancing advisor to the Academy. She had won some dancing prizes and she had risked dancers' limbs by judging competitions in the rain.

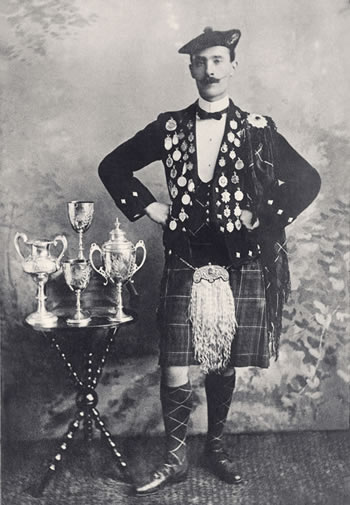

Mr Sutherland may have been approached to join the Academy about this stage; I can't remember. If he was, it was not as the principal dancing advisor, of that I am sure because never in his life was such an offer made to him. In any event, May Thorne Wilson,an ex-pupil of perhaps two or three years from his Dunedin days joined the Academy, subordinate to Mrs Cameron.

The Academy literature emphasises the teachers of May Thorne and Mrs Cameron, though tellingly it omits Mr Sutherland from the list for May Thorne Wilson. It would seem likely that May Thorne Wilson had longer with Mr Sutherland than she did with her touted teacher in Scotland. The women had about half a dozen teachers each, many of whom were Scotsmen in New Zealand. No information at all is provided of the teachers' competitive records in Scotland.

There is a problem in having several teachers because an amalgam of styles could result or just one style could dominate, so that some of the teachers effectively contribute nothing. If they all had the same style then most of the teachers are redundant. However, some dancers become better teachers than others, which does not invalidate the point.

When a dancer has several teachers the average amount of tuition time diminishes and so does the amount of knowledge disseminated. One teacher does not take up where a predecessor left off. The knowledge is thus not cumulative. The point to be made here is that having half a dozen teachers does not imply of itself that a pupil has a deep knowledge of dancing. May Thorne's and Frances Cameron's numerous teachers are not the firm foundation for the Academy that its literature implies. We will revisit this point in the discussion of the Scottish Official Board.

Ian Cameron, had connections to the Prime Minister, a Scot, Peter Fraser. Through the Prime Minister, Ian Cameron arranged for the effective secondment of May Thorne Wilson from the government Department of Internal Affairs to the Academy in its very early days. She might well have seen this as a good move in her government career in physical education.

|

|---|

William Sutherland |

However, the effect was to make her an Academy vassal under the patronage of the Camerons who could have dissolved the putative secondment just as easily as they had arranged it. As we have seen, Ian Cameron was capable of doing so. For one to have been shoulder tapped by the Prime Minister would have been prestigious; to have been seen to be uncooperative in the Academy or to resign the appointment would have been professionally disastrous.

The pressures from the work side of her life upon May Thorne Wilson to cooperate with the Academy would have been increased by the attendance of public servants, possibly her superiors, at an organisational meeting of the Academy held at the Cameron farm, I think. These pressures on her to comply would have remained after the secondment ended for as long as she was a public servant regardless of the colour of the government, because of the long memory of the Public Service.

May Thorne visited Mr Sutherland before Academy meetings in Wellington. They used to meet for breakfast in the Wellington Railway Station after she came off the inter-island steamer and he was well aware of her complete dissatisfaction with Mrs Cameron's knowledge of dancing.

May partially withdrew from the Academy for about six months early in the piece. As Madame Thorne, Highland Dancing Teacher, Thorne Wilson had a strong following in the far south. My impression is that the breakaway association that formed in Dunedin, only later to re-amalgamate, is from this period though I am not sure.

May Thorne Wilson's involvement in the Academy is significant because she was the only person at its centre in the formative years who could lay claim to being a Sutherland dancer. Whether her time with Mr Sutherland was before or after she danced in Scotland is unclear and unimportant. This is because if she learned from him before she went (a sensible thing for her to have done), then as her teacher he is responsible for her successes there. Alternatively, if she learned from him on her return it was because she had come to recognise his stature as a result of her being in Scotland.

Her connection with the Academy offered it some legitimisation as did Coila Barrowman-Richardson's later association. May was privately promoted in dancing circles as a suitable substitute in the Academy for Mr Sutherland. Legitimisation was necessary, though she was a poor alternative for the real authority that Mr Sutherland's membership would have conferred upon the Academy had he not found it contemptible.

It is of considerable interest that May Thorne Wilson's tuition from Mr Sutherland is not recalled in the collective memory of New Zealand dancers, and we shall return to the reason why this is so.

A charitable interpretation of May Thorne's part in the Academy is that she was under political pressure from work, was in a difficult domestic situation - her husband had died leaving her with two small children - that she really had had just a short time with Mr Sutherland 20 years and more before, and that she was simply overwhelmed by those about her.

The key point about the efficacy of her role is that the Sutherland style of Highland dancing never influenced the mode of dancing that was developed by the leaders of the Academy - not even remotely. Either she retained little of what she learned from Mr Sutherland or she failed in having it introduced by the Academy. Mr Sutherland publicised his severance with her in the Wellington Scottish societies once her commitment to the Academy became clear.

![]() Hilary Glasgow & Neil McPhee

Hilary Glasgow & Neil McPhee

Mr Sutherland was never a part of that movement though once or twice overtures were made to him by the pro-Sutherland faction within it in the 1950s. This was a group that was formed around ex-pupil Hilary Glasgow and Neil McPhee. Its influence was to wane.

The Glasgow family has been influential in piping and dancing circles as a result of their near 150 year and more association with the Turakina sports meeting. R. Hilary Glasgow started Highland dancing in Turakina with James Kinghorn, a Sutherland pupil from Scotland. On Kinghorn's departure for North America Hilary learned from Mr Sutherland, travelling to Wellington to do so.

I remember Hilary's father, "Old Bob," an impressive silver haired old man in a suit with a watch chain and a stick, and Hilary's uncle at the sports. Sometimes the sports would be held on Bob Glasgow's paddock behind the Ben Nevis and sometimes on the uncle's paddock. On sports day we used to stay at Edenmore, their farm in Turakina that has been in the family for generations. The family is still involved in the meeting and Hilary's daughter, Anne, played an important role in reactivating the community's involvement in the gathering some years ago. Hilary is the witness to the notes in the Scottish Official Board's book reproduced earlier. This sketch of the Glasgow family's involvement will reverberate at the end of this memoir.

Mr Sutherland understood that Hilary Glasgow and Neil McPhee were well motivated and were trying to redirect the Academy. Their association with it did not affect his long relationship with them and indeed that relationship was the driver of their motivation. He did, after all, spend his last years in the Glasgows' care. There was the expectation that he would be responsible to a sub-committee of the Academy, if he was to be involved at all, and that could never have worked given the personalities involved. His view was that no one on such committees had credible dancing backgrounds "beyond their own backyard." The organisers of the dancers knew his record too but they could not accept the authority of it. Unlike New Zealand pipers, who have always had a world-wide view of their music, the dancers did not accept Mr Sutherland's relevance to the New Zealand dancing scene. It was a cultural tragedy, and personal one too.

![]() Fates of Others

Fates of Others

He did not join largely because the Technical Committee (or some such name) consisted of people who, whilst practicing teachers and former dancers, were essentially New Zealand trained and therefore ill-informed for the reasons I mentioned earlier. About this time Davey Bothwell, and a little later Bertie Robertson, were associated, to no effect. There were also the severe personality difficulties dating almost to Mr Sutherland's arrival in Dunedin to which I have already referred. Mr Sutherland felt that the members of the "Technical Committee" did not have the knowledge necessary to determine how the dances should be performed. They did not. Nor, he felt, were they in a position to debate dancing with him, and they were not.

He correctly read the purpose and consequences of his being subordinate to the Technical Committee. He would be under its control in matters of dancing technique so he would have had little practical influence. The experiences of Davey Bothwell and Bertie Robertson would confirm this assessment. In the Academy's vision, the value of Mr Sutherland's membership would have been in its use as propaganda, so he denied the Academy that use to it.

There has already been an allusion in the "Introduction" to the influence of ballet on New Zealand Highland dancing. The source was through two pupils of the brothers Duncan S. and Donald G. MacLennan, the London MacLennans as I call them in their biographical details, see Introduction. These Highland dancing teachers were involved with ballet in the United Kingdom.

![]() Ballet & Dorothy Parker

Ballet & Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker was a pupil of Duncan's in Gisborne, New Zealand, learning a variety of dance forms from him, and David Bothwell was certainly a pupil of theirs, probably of Donald's. After leaving his teacher Bothwell had an association with a Danish ballet company though his capacity there and its duration are unknown. Davey's influence in the Academy was transitory in the 1950's and is notable only because of the formative period in which it occurred. Parker was influential in the Academy over a long time.

Parker's training in other dance forms may be taken as a primary influence early on in the emergence of Academy dancing. Doubtless there are other Academy accolytes with backgrounds in other dance forms similar to Parker's, President Geddes for one. But her impact in the importation of a ballet technique was at a time when the style was being laid down and so was significant.

Apart from the appearance of some obviously imported movements, unobjectionable in themselves as artists must always be extending limits, the influence of ballet upon Academy dancing is seen in the timing of defining movements like shedding, the back beat and the various shakes as in the step shakafoot.

There is also the grip in reel swinging where it became near the elbow and there is the inversion of roles of the inside and outside foot with its extension in that movement, all a la ballet . Mr Sutherland's style in these movements has been described in the section, "Teaching and Technique." These changes helped alter the nature of Highland dancing in New Zealand.

The addition to New Zealand Highland dancing, qua Academy, of corruptions in timing from ballet, makes perfect sense: The Academy founders lacked a knowledge base in Highland dancing and ballet was sucked into the vacuum.

The problem is not in the introduction of different movements. It is in the Academy's uncritical acceptance of ballet timing. The music for ballet has a different and more variable structure from that for Highland dancing. The cross-fertilization failed because the timing of the introduced movements was not adapted to the timing of bagpipe music for Highland dancing. A distinction can be so great that a gap is unsighted. Even had they seen this clear point of musical departure, the Academy Boeotians lacked the technical skills in Highland dancing to adapt ballet movements to the timing of the Highland dance form. This maladroitness contributed to the clear break in dancing style that the Academy introduced.

![]() Davey Bothwell

Davey Bothwell

Davey Bothwell has a great nephew living (and dancing) in Scotland. Great Nephew Ian Bothwell writes that Davey had...

An Irish father, mother from Grantown-on-Spey, brothers and sisters all brought up in Dundee, David was the youngest of 14 children the eldest of whom was 29 years older than him, he was the only one born and brought up in Lanarkshire after the family moved to Coatbridge after his father had retired from the Dundee police. I don't know how, why or where David learnt his dancing though he did have a brother who was a piper in the Scots Guards. David, himself, served in the Scottish Rifles during WW1. The second son, William, 22 years older than David was a footballer who once officiated as a linesman at a Scottish FA cup final and who was a founder member and long time secretary of the Scottish Juvenile Football Association. He became manager of the Glenboig brick works which is where most of the sons worked. How then did dancing become David's thing?

Despite his death certificate stating that he was a bachelor (he died alone in some squalor), David did marry (in 1914) at which time he gave his profession as a 'Music Hall Artist', he soon had a daughter who started school in Scotland and he has great grandchildren living in Hamilton, New Zealand who know as little about him or his dancing career as I do. We believe that his wife and daughter both died relatively young but if anyone can remember them, it would be nice to know.) Ian Bothwell's question about Davey's teachers has been answered - he was a London MacLennan dancer and the consequence of that has been examined. Given his birthdate 1895, his army enlistment date of 1915, and the fact of his competing in the New Zealand in 1926, a question is raised about how much competitive dancing Bothwell could have done in Scotland.

In a further letter Ian Bothwell states that:

His relatively short stature was also of interest as both his parents were quite tall. The Dundee police sergeant was a very large man and I'm told that even his mother was close to six foot. Several of his brothers, including my grandfather were over six foot with very manual jobs in the brick works and had joined the Scots Guards, whereas David would have been too small and had to settle for the Scots Rifles.

David's father died when David was six and his mother remarried when he was twelve. She appears to have abandoned her large family and only the youngest daughter appears to have moved with her to a new home in Blairgowrie (not too far from here). I'm hoping that the 1911 census (to be released in 2009) will tell me who became responsible for David. I'm also hoping to confirm the exact date at which David emigrated as the ancestorsonboard.com database increases. To date, they have listed emigrants from UK ports up to 1919 but David is not included.

Lyn Collins writes that:

David was my husband's grandfather. David had one daughter Elizabeth, who we believe came to NZ with David at about the age of 12. The interesting thing is that Elizabeth never seemed to have had a mother in NZ, well none that was ever spoken of or known by my husband. Elizabeth died when my husband, John, was only 9, and he had very little contact with David while he was growing up, there was some bad blood, it seemed between John's father and David. John also had an elder brother Barry who had more contact with David being 5 years older than John and played the pipes, doing the Highland games etc., with Dave. I did know Dave when John and I got married and he was living then in Waihi with George. I thought him an interesting and colorful person, and he seemed to think I was o.k., being a Campbell, although I know people who would not think the same way! I agree with your observations of David and am sorry that you did not know anything about his wife or daughter, which is our main interest.

I had written to Ian Bothwell the comment that Lyn Collins refers to:

Davey was an effervescent individual with a nice Scots accent. He was slim, about 5''7" in height with dark hair, slightly curled when I knew him. He was of very a neat appearance with aquiline features and quite rosy cheeks and handsome teeth. He always seemed to be in a bit of a rush.

Ian Bothwell has since determined that Davey left Southhampton aboard the Arawa on 11 December 1925 with his wife and 10 year old daughter Elizabeth.

Davey was homosexual at a time when this was illegal and New Zelanders were intolerant of those with that orientation. George Mathews, his partner in Waihi who Lyn Collins refers to, used to flounce around the sports grounds in a very colourful kilt.

David Bothwell was important to me because apart from Bertie Robertson, Davey was the only dancer around who had been trained outside New Zealand. I therefore wanted to engage him in conversation about the technical aspects of Highland dancing.

He was always evasive and difficult to pin down and when I did manage to raise a topic with him I found him wanting. For example on side cutting, where he said that the dancer should sway slightly from side to side. This eases the weight transfer but it is a motion that is alien to Highland dancing and destroys the ground-based nature of this elegant movement, diverting attention from feet moving with fluid precision close to the floor.

I recall a small number of Academy dancers trying to side cut in the hornpipe while rocking from side to side so perhaps this came from Davey. Apart from my own attempts at the step the movement had all but vanished by the end of the fifties. Around then I saw Coila Barrowman-Richardson's son making a woeful attempt at the step at the Wellington Provincial Highland Games. Coila never learned side cutting from Mr Sutherland - I attended every one of her lessons from him - but by her son's time she had lost or discarded the Sutherland style, perhaps as May Thorne Wilson did.

Opportunities are often lost and Mr Sutherland's involvement with the Academy did not eventuate. One factor was that the presence of an expert would have thwarted the hierarchical ambitions of the enthusiastic amateurs in the Piping and Dancing Association. The non-dancers in it really saw little need for him. But the dancers in the Academy would have found their inadequate foundations laid bare had he belonged, so they were not keen either. The conjunction of these factors resulted in terms being placed on his potential membership that locked Mr Sutherland out. His relationships with pipers were so much better because they knew from the immigrants among them of his standing in the wider dancing world, and they accepted it.