![]() Teaching and Technique

Teaching and Technique

![]() Important Pupils

Important Pupils

Mr Sutherland never had large numbers of pupils, though he taught almost continuously in New Zealand. There were two reasons for this, one concerning his style of teaching. He never taught en masse. He would have two or at most three pupils at a lesson. For reel dancing, to make up the numbers, he would have either to ask some non-pupil along or, if he happened to have four pupils, arrange a special session. The techniques of reel dancing were taught individually, as was everything else. These invitations, I believe, are the source of many claims by dancers to have been taught by him, when they were nothing of the sort. Sometimes he would ask them to dance and make a correction or two. In fact, in private they were used as examples of how not to do things - with explanations as to why they were not to be done that way. Mr Sutherland had few pupils and many of them did not last very long, often because they could not accept the uncompromising discipline of the dance. This individual manner of teaching limited the number of pupils he could take as he taught in his spare time.

The second reason for the limited number of pupils in the 1920s and 1930s was that he was very choosy in who he took on, the ill-will he suffered in Dunedin being a factor in this. Among his pupils when he was living in Dunedin was May Thorne Wilson who taught successfully in the South for some years. Hilary Glasgow was a pupil of Mr Sutherland's, as were June Scott and Coila Barrowman-Richardson after Mr Sutherland moved to Wellington. The first two were before my time and Coila, whom I remember well at lessons, learned from him for perhaps three years around her middle teens. James Kinghorn of Turakina was a pupil of Mr Sutherland's when they were both in Scotland. Hilary Glasgow started dancing with Jimmy Kinghorn in Turakina.

May Thorne Wilson had perhaps two or three years' tuition, if that, from Mr Sutherland because he arrived in Dunedin in 1923 and was living in Wellington by 1926. Davey Bothwell is said to have had lessons from Mr Sutherland. Davey lived in Masterton for a period in the late 1920s so it would have been possible though quite difficult in those days for him to have had lessons in Wellington. Mr Sutherland however, never acknowledged him as a pupil though his name would come up in conversation on occasion, in connection with the relationship between ballet and Highland dancing. Davey learned dancing in London from Donald G. MacLennan, mentioned in the Introduction. We will return to an effect of this influence on Bothwell.

All of Mr Sutherland's acknowledged pupils started with other teachers and he had to do a great deal of work with them in ironing out bad habits which had a tendency to return. An infamous remark of Coila's was, "That's the way we do it up North and I can't see anything wrong with it!" Coila was discharged and came back but the continuing problem of the Academy divided her loyalties and ultimately Mr Sutherland excluded her. He thought that she was having lessons from someone else (possibly Adeline Burnet-Hobbs - my father taught Henry Hobbs the pipes and I heard Henry playing in December 2001, aged 83 years). It would have been easy to pick the influence of a second teacher upon the dancing style.

Others I remember him teaching in the 1940s are John McMillan and sisters Marion and Ruth McDowall. Only John learned for more than two or three years. All of these pupils used to travel with their parents from Palmerston North. Margaret Laurenson of Shetland Society connections was another pupil for perhaps five years, a beautiful dancer in the understated Sutherland way, who made the New Zealand Reel Team. She withdrew from the dancing scene as her family became sickened by the situation that was developing.

I was at lessons with all of the last group at different times. At this time until around 1948, lessons were held in the gymnasium of the Wellington Central Police Station. Classes were held there through the good offices of Neil McPhee, a policeman before he started up a Scottish shop with his brother Allan. Early in the piece the lessons were given in the Taranaki Street Police Station in a gym, where there was a boxing ring but the girls would not box with me. The ring was easy on the feet and I would have preferred to dance on it but there was nothing doing.

![]() Lessons

Lessons

My parents asked Mr. Sutherland to teach me dancing at a Wellington Caledonian Society social. He asked to see me and had me walk away from him across the hall to check my coordination, my physique and to see if my legs were straight. The occassion is retained on the edges of my memory.

My lessons started in August 1943 when I was five years old. I well remember going with Mother by train from Lower Hutt, then by tram to the Salvation Army Hostel in Vivian Street, Wellington. There, for all the years of my lessons, Mr Sutherland lived in a tiny second or third floor room cluttered with his possessions. It had a stand-alone cupboard, a single bed and a chair upon which Mother sat for the first of them. There was barely enough space for me to stand near the cupboard mirror. He did not like dancers to use mirrors as it made them look downwards and he thought that it affected their deportment.

He seemed to be in his fifties then, though he was 65, and he always wore impeccable dark, single-breasted tailored suits of quality stuff with a starched collar and gold tiepin. The pin was worn under the knot. He wore a pince-nez for reading and sewing, the angle of it changing as his eyesight modified. His black shoes were always shining. He was about five feet nine or ten inches in height, tall for a dancer in those days, of upright though relaxed posture with soft, fair Highland skin and features. He had blue eyes, a little rheumy in later years when they lost their lashes, and the Highland accent – with its consonants softened.

He did not have the Tongue. His singing voice was a pleasing tenor. He did not have his mustachio when I knew him. His frugal habits and long working life left him comfortably off.

He sometimes made substantial cash gifts to his daughter and they were regular in their correspondence. Upon her marraige he gave her 10,000 pounds, enough to buy two or three houses in those days. It is hard to see how such a large sum could have been accumulated from a piece-work tailor's earnings so I infer that his winnings in Scotland from Highland dancing were substantial.

He attended the Basin Reserve regularly to watch cricket and soccer matches without supporting particular teams. Contact was maintained with the expatriate and New Zealand Scots communities through his regular attendance at the Wellington Caledonian Society, the Shetland Society and sometimes the Gaelic Club and the Burns Club. He enjoyed these socials, mingling with those who were interested in the Scottish arts. Prominent pipers, dancers and teachers along with Piping and Dancing Association and Academy members in the region attended these inglesides. People enjoyed his company and respected his knowledge of dancing, piping and Scottish lore. I danced often at these evenings.

Below: Bruce, who made the sword and Ewen aged 11

Mr Sutherland often told me that I was the only pupil he had ever had whom he started from the beginning, and that he taught me for longer than he had taught anyone else. Everyone else had made a start with other teachers. I was his final pupil. He had none other than me from 1948. He gave me a large cake of Cadbury’s chocolate after every lesson and once I lost it down the back of the seat in the tram. I was allowed one piece of chocolate after the lesson, because it wasn’t good for little boys. My view was that this was a theory that should be tested. Mother ate the rest during the week. He never charged my parents for lessons and as far as I know he never charged anyone else, though thinking about it, he may have done so in Scotland. I used to have to put half a crown by our wireless for him to pick up for his train fare when the lessons were conducted at our home.

I was taught three stretching, strengthening and limbering exercises, which also trained the feet outward and about half of the ground positions at the first class. All of my subsequent practice and future lessons started with those exercises which Mr Sutherland always watched me perform. I did them every time that I laced up a pair of dancing shoes and I never had an injury in the years that I danced.

When teaching, Mr Sutherland used to stand beside the dancer, in line with the second postion occassionally going a little behind or forward to check something. For a start, as a small boy, I used to turn to face him and Mother would have to turn me round so that I was side on to him. I stand in his way myself when watching dancing competitions, though there is no pleasure in that in a New Zealand which squanders talent.

My learning process was unhurried and thorough. I spent twelve months learning six steps of the Highland Fling, which I think is the most subtle of the dances. I started to learn backstepping when I was rising seven. At the beginning I learned holding with both hands onto the back of a chair for balance and never was I allowed to lean on it or to pick up speed. More importantly, absolutely no attempt was made to get me up on my toes in all the years that I learned from him. That was something he considered too demanding for a child’s soft foot bones and would come naturally as the feet strengthened. It did.

In his later years Mr Sutherland used to hold onto a chair with one hand for balance when he was showing me a new step or movement. Before that he would dance unsupported.

He had elegant feet. He was able to spring from the foot without gathering himself, doing so in a way that I have never seen even ballet dancers manage. His movements were minimalist, there was no flamboyance, just perfection in technique and timing, even at that age. Early in my tuition he would dance the first two steps of the fling but as he aged he never danced more than a few bars at a time. He taught Mother and me some traditional Highland Ballroom dances, that bear little relation to the way that they are danced in Scottish Country Dancing. His father-in-law, a Mr Mathieson, was a dancing teacher in Aberdeen and I speculate that Mr Sutherland learned the ballroom dances from him though he may have learned them from Clementina, his wife. In any event they were marvellous dances that he taught us.

He had a very effective way of “dancing” with his hands. In demonstrating with his hands he could slow things right down, defeating gravity, while teaching when in a movement the lift was to come. This allowed him to demonstrate by exaggeration the correct way of doing things. He would sing slowly as he did this so I would get the phrasing. Using this method, he would show Mother and me how the different dancers in Scotland, naming them as he did so, performed different movements. Through this I learned that dances could be interpreted in different ways. This instruction by hand dancing was done while I was having a spell between dances. It was a very important part of the lessons because through it I learned the “why” of dancing.

![]() The Swing in Reels

The Swing in Reels

He taught me to swing in reel dancing in a way utterly different from the way it is done now. I would swing with him and I recall, in a detail that is still almost physical to me, the sensation of rhythm and the meaning of the music in his swing. I learned that swinging was cooperative in that one dancer must support the other. I also learned the odd dirty trick for use when the companion swinger was not helping. These defensive measures turned out to be useful to me when competing, for reasons that you will be able to infer as you continue with this memoir. When he wanted to watch me swing, Mother would dance with me. On a celebrated occasion, to my delight at the time, the lesson on swinging turned into a lesson for Mother – who ended in tears. The point being that one person could scarcely swing correctly if the other was not doing so.

The technique of reel swinging was for the dancers to stand in the first position, facing opposite directions with the outsides of their bodies a trifle advanced and the inside shoulder in front of, and slightly to the side of, their partner’s. They firmly grasp each other as high as possible under the armpits with elbows fully bent, the one drawing the other’s arms into their ribs. This is a very secure position, the closeness of the dancers offering advantages in rotational motion.

The start of the movement is its key. It starts with a small step forward towards the fourth position with the inside foot. The outside leg is then advanced to a pronounced false second position. This completes the movement. The phrasing is that the first beat in the bar, when the inside foot moves, is strongest. The outside foot is the embellishment.

It would greatly help pipers’ understanding of reel playing if they could swing. Major emphasis was placed on the music in each dance. I learned that my dancing was always to be my interpretation of the music and the way the piper played it. There were key aspects of phrasing in each dance which were special features to be preserved because the effect of the dance comes partly from them, as with reel swinging.

Good pipers and dancers lift their combined performance, but the piper must watch and the dancer must listen. Dancing to a variety of tunes is important in Strathspey and the reels though not in Ghillie Callum and Seann Truibhas which have particular tunes, one for the swords and two for Seann Truibhas. Pipers nevertheless, can play those dance tunes differently from each other. The piper's introduction to a dance tune is important as it tells the dancer how the piper is going to play it and gives the dancer time to plan the dancing interpretation of a tune. It was an advantage to have been brought up in a piping household.

![]() Phrasing

Phrasing

The phrasing of movements was central to Mr Sutherland’s teaching. Each dance had its own counting, for example, the counting for the fling is &1, &2, &3, &4 where the ampersand indicates a spring and the integers are the beats in the bar when a position is reached. This counting carries into particular movements like shedding, backstepping and the shake in shak-a-foot. From it one knows exactly when in a movement to apply the lift. The counting itself is phrased and is usually sung to a Strathspey or other dance tune. Mr Sutherland’s phrasing of Strathspey should be recorded for its marvellous subtlety.

The first and defining step of the fling can be used to demonstrate it. The first beat of the bar is by far the strongest, the dancer holds the second position. The count is & for the spring then 1 for the first beat where the dancer reaches the second position. The second beat is also long where there is another pause in the fifth aerial position, the count is & for the spring and 2 for the fifth aerial. The lightest beat is the third, &3, and there has to be some emphasis on the fourth beat, &4, to register the completion of the shedding movement. When he was competing himself Mr Sutherland would hold the second position at the very beginning of the dance for so long as to almost break time. This was for dramatic effect – and to catch the judge’s eye.

“Struan Robertson” lends itself to this phrasing, so does “Arniston Castle” and even a simple tune like "Because He Was a Bonny Lad". My Father learned this phrasing from Mr Sutherland. He and a few of his pupils are the only pipers that I have ever heard play it this way. It puts life into the dancer.

This phrasing is not much use unless dancers have proper technique for shedding around the leg. Shedding is a movement that is done from the knee. The dancing thigh is sqaure though it does not move. This means that the dancing foot follows a natural arc between the fifth and third aerial positions around the calf of the grounded leg. The dancing foot is to be pointed. Whether or not the toe of the dancing foot extends beyond the shin of the grounded leg is of little moment as it partly depends on the the length of the dancing foot . Mr Sutherland was very clear on this point as there was controversy about it within the New Zealand Academy of Highland and National Dancing and around the boards in the 1950's.

Phrasing is important in backstepping too. Taking the customary second step of the fling, the end of the first bar of the second measure takes the dancer to the third aerial position. The first and strongest beat of the second bar marks the start of the backstep and brings a very deliberate fifth aerial position. It is then, and only then, that the ground foot provides the sharp spring. The rhythm of the beats that has been explained carries through all movements of the dance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Presented by N. Mackenzie Forbes New Zealand for Most Points Highland Dancing Lonach Gathering 1914 Won by W Sutherland |

WCS Presented by N Mackenzie Forbes Highland Fling Chmpshp Wanganui won by W Sutherland 1927. |

Most Points Highland Dancing Presented by N Mackenzie Forbes New Zealand Won by W Sutherland |

|||

|

|

|

|

These medals are of interest because of their connection to Neil McKenzie Forbes. McKenzie Forbes placed fourth in the Highland Reel at Aboyne in 1896, a little before Mr Sutherland’s long term grip on the event. He was a Scot who was well liked in Wanganui where he had, I believe, a successful business as a jeweller. Mr Sutherland won medals that M’Kenzie Forbes donated to games in both Scotland as early as 1914 and in New Zealand as late as 1927. I take TCS on the 1924 medal to mean the Turakina Caledonian Society |

|

MCS Presented by N Mackenzie Forbes Sword Dance won by W. Sutherland 1927 |

Presented to TCS by N Mackenzie Forbes Dancing won by W Sutherland 1924 |

||||

![]() Today’s Dancing

Today’s Dancing

As a general comment, much of the effect of Highland dancing comes from the knowledge of the positions that mark the commencement and the conclusion of the various movements and where in them to apply the spring. It is noticeable how this principle is not observed in New Zealand though only Sutherland dancers used to apply it. Dancers now seem to get off onto the next movement before properly finishing its predecessor.

There are reasons why the current dancing method is impoverished. The first is musical. When the piper is playing a tune with any passion it does not run like water from a tap. There is punctuation in the phrases of the music. Often the phrases in pipe music do not coincide with bars though in the standard dances they do.

More prosaically, music comes in bars and often enough a dancing movement coincides with a bar. Short movements, like a shake, do not take a full bar. Bars of course are a succession but they provide structure to the music and so to the dance. When the dancing movements are run together, the dance becomes one long sequence of bounces. Ending dancing movements properly removes the monotony of the bounce.

The overall impression that is left by this lack of phrasing is that of mechanical repitition. Highland dancing has a symmetrical structure, left and right, to each step and that is as much repetition as we require. Marking the ends of dancing movements provides variety.

This is not to say that the dancer is to pause at the end of each dancing movement. It's just that there are ways of completing a dancing phrase. Sometimes it may be done by the slightest lowering of the heel of the ground foot. Or, a slightly smaller spring at the appropriate place will do it. A subtle hand movement can be an indicator. How the end of the movement is registered depends largely on the movement itself.

Dances are structured as dance tunes are structured. A step ends at the end of a part. Take the obvious strucutral breaks in the Fling, for example, where hands and head positions change as the dancing foot changes in shedding. Here the change in the dancing foot coincides with the end of a bar one quarter of the way further through the measure each time. The dancer puctuates those bar endings in the way we have described and according to the Strathspey count. Steps in all dances should be assembled so that there are relations, echos and contrasts, between them. Dancers have different attributes, physical and technical to build a dance around.

![]() Backbeat and Shakes

Backbeat and Shakes

There is technique in apparently simple movements like the back beat in Strathspey and in the pas de bas in the swords and other dances. The back beat in the fling, in the step shak-a-foot and elsewhere, was taught to me consonant with the Strathspey rhythm and entirely differently from what is seen today. The back beat is a distinct motion, not one that is run into others. It has something of a lifting motion to it.

To commemorate the coronation of King George V Edinburgh Coronation Festivities Highland sport dancing Sheuntruibbias won by W Sutherland King George V & Queen Mary

The shake itself in Strathspey starts in the fifth ground position, though it is easier for children lacking in precision to use the third ground, and ends in the fourth aerial. The Strathspey timing and counting that has been explained is maintained in the backbeat and the associated shake and is central to it. It explains why the shake itself begins in at the fifth ground and ends with the fourth aerial.

Since the 1950's dancers have under-emphasised the back beat and fifth ground position of the shake, getting off the fifth far too quickly. The distinct backbeat combined with this way of shaking is quite a different technique, providing variation, rather than the boring and mechanical bounce that is the result of the current technique.

![]() Shuffle

Shuffle

The technique of the shake is different in the shuffle in Seann Truibhas than in Strathspey. Elevation is required in this movement in Seann Truibhas. But each shuffle starts and ends with the fifth ground postion. It is done using the fourth aerial position, not the intermediate fourth aerial.

To explain the movement, consider just a single shuffle, say the second shuffle in the movement. After the first shuffle the right foot is in the fifth ground position ready to start our lonely second shuffle. There is a good spring to the fourth aerial for the left foot which is now the dancing foot, though the left foot is held rather low in the fourth aerial. Back to the fifth ground. Now we are ready for the shake in the movement. The shake is not fully extended to the fourth aerial and the dancing foot goes back to the fifth, completing the shake. Once we are back to the fifth ground our solitary shuffle is complete. Completion is marked by the suggestion of a depression of the left, dancing, heel. Do not overdo this lowering of the dancing heel. This depression is natural as the feet are changed with the spring into the aerial fourth of the next shuffle.

The general idea of the movement is that the dancing foot comes back to the ground foot; it is not a kick away from the ground foot as one sees nowadays. This kicking effect is unseemly and it arises because dancers use the fourth aerial as the beginning and end of each individual shuffle rather than the fifth. We used to watch it incredulously and call it "horsekicking." I still do.

Horsekicking was a product of the Academy, an outcome of a process to be described in later chapters. Before, say, 1950 New Zealand dancers did not shuffle from the fourth aerial position in the way that they later did. Nor did they shake in the later way in shak-a-foot. They did not have the timing of the second shake in the shuffle quite right - it has do be done a little quickly - but the shuffle did commence properly in the fifth ground postition. The back beat in the Fling was distinct prior to 1950, as it should be, but the shake was executed in a fourth aerial position that was too high off the ground and with a motion of the thigh instead of from the knee. These matters of dancing technique were unknown to the hoi polloi but the difference in effect was important in distinguishing Sutherland trained dancers. It required knowledgeable teaching and practice to achieve.

There are reasons why the shuffle is to be done in the way I have described. One is the sheer elegance of the method. Sometimes Mr Sutherland would have me dance an entire step by just shuffling followed by another equally elegant step of pure side cutting. This sequence requires poise and control but it is satisfying to carry it off without error.

Another reason for the Sutherland form of shuffle is to provide contrast within the dance, particularly in the opening step of Seann Truibhas. There are different ways of dancing this circular step, each involving pronounced aerial fourth positions. One variant invokes the rear fourth aerial.

In some of these ways there is a repetitive sweep away from the fifth ground position to the aerial fourth. Dancing the shuffle as described is a reverse action to this sweep and provides a contrast to it. Contrast is is also the reason why the aerial fourth position is held low in the shuffle. The couterpoise to the sweep provided by the Sutherland shuffle is typical of his dancing artistry.

Shuffling in the same way in the second step links the second step to the first. The shuffle also contrasts with the traverse of the second step which is danced low to the ground balancing the aerial character of the first step. The count in Seann Truibhas is &1, &2, &3, &4, Using our second individual shuffle, the "&" is the spring from the fifth ground postion , &2 completes the second individual shuffle and the whole movement completes at &4.

I should mention of course that shuffling also features in the reels where the short burst of high cutting in a step can often be replaced by a shuffle. Dancers able to do both of these movements properly have an embarassment of choice.

![]() High Cutting and Side Cutting

High Cutting and Side Cutting

Mr Sutherland always danced the pas de bas with an open second aerial position. He recognised that other dancers did not do it this way but the difference was dramatic. I believe that he brought this innovation to Highland dancing. The same was true in high cutting, where the first cut was done with a fully open second aerial position of the dancing foot, the opposing leg naturally extending a little sideways, but not deliberately so, when the dancer was aloft. Each cut terminates in the second aerial fifth. The timing of the spring is again critical. It takes a good and powerful dancer to do this.

Side cutting is a movement that is related to high cutting and the techniques are similar in the two movements. "Ground cutting" is an older and in some ways better name for the movement because it is done close to the board as opposed to in the air.

Just as high cutting may be done with either two aerial fifth postions or with the aerial third position replacing the second aerial fifth, so can side cutting. Here, instead of using two rear ground fifth positions the second rear fifth can be replaced by a third ground. In the sword dance, Mr Sutherland used to teach dancers to use the third aerial just once in the first step, at the third point of the sword. He never overdid things in his dancing.

I used to dance these movements both ways. Noone that I can remember was sidecutting in New Zeland by the late 1950's and there was a good deal of interest in the movement among my competitors. To keep the people guessing and to hold the judge's attention, I would side cut one way in one dance and the other way in a second dance. Sometimes would stick to one way for the day, so as not to give too much away.

![]() Pipe Music

Pipe Music

Mr Sutherland used to whistle tunes for me to dance to; he had a huge repertoire of pipe tunes at his disposal, known by name and accurately whistled. Though not a piper, he was very knowledgeable about the little music. This is corroborated by Ian McKay in a private communication dated 13 March 1995:

“I can also confirm, at least in part, your recollections of Willie’s knowledge of pipe music. I remember him singing to me the fourth part of Edinburgh Volunteers in a style which he described as played by John MacDonald of Inverness. I still recall the particular setting, and it is not one that I have ever seen published or written.”

Apparently in the train on the way to the games he used to sit with pipers discussing pipe music, the best of whom he thought was Pipe Major William Ross, Scots Guards.

When the dancing lessons were later held at my home, Mr Sutherland would afterwards pass on the interpretation of marches, strathspeys and reels, with the music – which he could follow – to my father, Bruce William McCann, a well-known piper in the 1930s and 1940s. I remember them going over Ceòl Mór with the Piobaireachd Society’s collection on Father’s knee, he with the practice chanter and Mr Sutherland singing. When my father was away for some time, he arranged for his pupil (my friend Peter F. Dyer, now of Ihakara in the Horowhenua), to have guidance in the Big Music from Mr Sutherland.

He would come every Sunday for a roast midday dinner to be followed after a break with a two-hour solo lesson with Mother present. (When the train timetable changed he came a little later and stayed for the evening meal. I used to meet him at the station and return to the station with him.) He liked to have her there so she could ensure that the ensuing week’s practice reflected the lesson. In the two-hour lesson I would dance the fling twice, invariably, and all of the other dances at least once with some of them repeated. It could take quite a long time to get through a dance when the performance was not up to scratch. New steps or movements were taught in isolation. When I was about 20, my friend Terence G. McKelvey, of Hamilton, was permitted to watch the lesson for the last two or three dances provided he kept his pipe out of sight.

I practiced under Mother’s close supervision six days a week from 7.30 am to just before 9 am, as we lived close to school. This regime continued until I started secondary school, when I practiced after school. There would be a short break in the Christmas holidays but not too long because summer was the peak of the dancing season.

The lessons always emphasised precision of technique and phrasing as these are the means the dancer has of expressing himself. The suppression of effort was important. He had a great variety of tasteful touches dotted through the dances, many of which he passed on to me and I which have not seen in Highland dancing since.

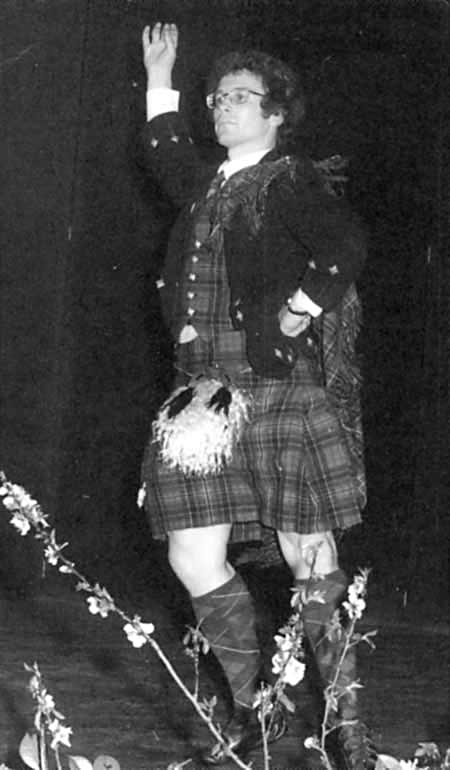

In thinking of his dancing vignettes it crosses my mind that I commence Seann Truibhas from the rear fourth position, with arms in the fifth and head askant, standing obliquely to my audience. This is dramatic as the dancer adopts this pose during the introduction to the dance, making a dynamic or non-static commencement. Another morsel is shown in the photograph of the unfit 23-year-old dancing Seann Truibhas. Backbeats largely replace springs in this most beautiful step. It begins with two false second positions in succession and a back beat between them. I am flicking the foot from the understated first one. The second is done with the heel, which is a surprise, and is why the first is to be understated to catch the attention but not to dominate the surprise. The step finishes with an elegant reverse shake in the aerial fourth. Compare the wrists of the man in the kilt and the man in the trews.

Ewen McCann, Seann Truibhas, 1962

Mr Sutherland was very patient, kind and understanding. He never lost his temper with me. His standards were always unrelenting, no slip was ever allowed to pass uncorrected. He would go over an error, or new wrinkle, or step three times with me which I would correct, or practice, the following week. He would remember at the next lesson what it was and the item would be isolated and the process repeated over the weeks until eventually the new step or procedure was considered satisfactory and added to the repertoire. Only now can I appreciate the prior thought that he gave to my dancing lessons. Mother was always a close participant in the lessons and practice.

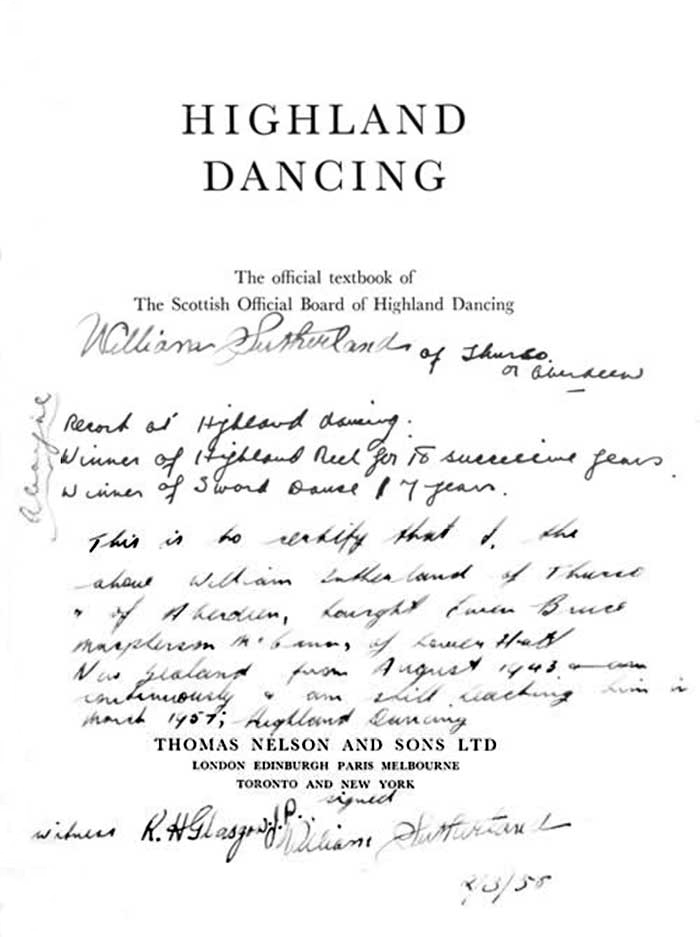

My lessons continued weekly for 11 years until I left secondary school. Thereafter they continued monthly at my parents’ house until I was twenty-three years old when Mr Sutherland retired and left Wellington. The documentary evidence of my first 14 years’ tuition is seen written in Mother’s hand and my own from student days on the accompanying frontispiece of the book of The Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing.